We create infrastructure to facilitate development. But, when infrastructure is well-designed and well-executed, it increases the price of nearby land. This pushes development (particularly affordable development) away from infrastructure to cheaper, but more remote sites. This “infrastructure conundrum” is one cause of urban sprawl that creates many environmental and fiscal problems.

In this article, we’ll discuss how the economics of sharing can help solve these problems and promote more prosperous, sustainable and equitable communities.

Governments pay for public goods and services by levying taxes and fees. “Fees” are related to either the benefits we receive or to the costs we impose on the government. “Taxes,” however, bear little or no relationship to the benefits received or costs imposed.

Sales taxes raise lots of money. Governments could pay for, say, drinking water with a sales tax. But typically, governments charge a per-gallon fee. The more water we consume, the more we pay. There’s some fairness to that. When we pay by the gallon, we tell our children not to leave the faucet running. And when we have a leaky faucet, we see our money going down the drain. This motivates us to fix the leak. If we paid for water with a sales tax, we would not be as motivated to conserve water or fix leaky faucets.

Thus, “user fees” can promote both fairness and efficiency. So, if they’re such a good idea, why don’t we pay for the entire cost of public goods and services with these fees? Simply put, if we did, the fees might be so expensive that only the very rich could afford them. And many of the benefits of clean water (for instance, public health) can only be achieved if everybody can use it. Massive investments in water purification and distribution wouldn’t make sense if it was only being consumed by a few wealthy people.

So how do we make up the difference between these affordable user fees and infrastructure costs? Governments often rely on general taxes for this purpose. But, over-reliance on general taxes can allow “invisible beneficiaries” to reap windfall gains, creating the “infrastructure conundrum” mentioned at the beginning of this article.

To discover the “invisible beneficiaries” of infrastructure investments, let’s return to the drinking water example.

Think about two vacant lots on opposite sides of a vibrant big city. Both lots are the same size, the same distance to downtown, have the same zoning and the same demand for development. The only difference is that Lot #1 has water and sewer pipes at the property line. Lot #2 does not have any water or sewer pipes within a half mile. Which lot is more valuable?

The answer is Lot #1. It’s is more valuable because it’s cheaper to develop. The builder doesn’t have to dig a well and create a sceptic system or extend the pipes (as would be required at Lot #2).

But is Lot #1 more valuable because of anything that the owner has done? No. Lot #1 is more valuable because the water authority has built (and hopefully maintains) pipes up to the property boundary. Thus, the owner of Lot #1 should pay the water authority for value that the water authority creates on that lot. This wouldn’t be a user fee. It would be an “access fee.”

Typically, communities fail to collect adequate access fees. This isn’t merely a harmless oversight. Inadequate access fees result in windfall profits for landowners near new or improved infrastructure. The ability of private landowners to appropriate publicly-created land value is the fuel behind the parasitic practice of land speculation.

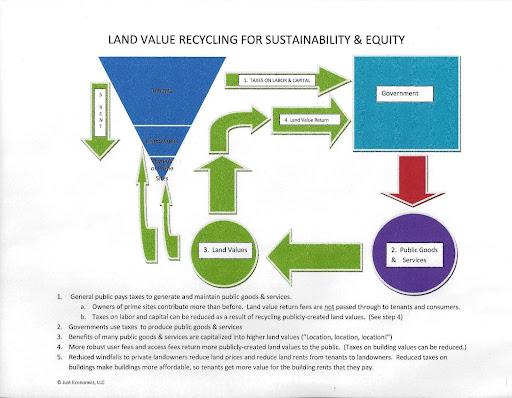

In the following diagram, we can see the money flows associated with infrastructure investments:

As we can see only a small fraction of community-created land value is returned to that community. In fact, many communities are giving away 80% to 90% of the land value that they create. And, not surprisingly, the best-served land in most communities is owned by very wealthy individuals and corporations.

What this diagram also shows that most taxpayers pay for infrastructure twice. First, they pay taxes so that the government can create the infrastructure. But, if they want to take maximum advantage of it, by locating their home or businesses nearby, they have to pay a premium (in rent or purchase price) to occupy that valuable location.

The remedy for this situation is to charge more robust “access fees” to landowners who benefit from public infrastructure. The following diagram illustrates how returning publicly-created land values to the community changes the money flows from infrastructure investments:

Returning community-created land values to a community constitutes the “economics of sharing.” By making land value return more robust, infrastructure investments become financially self-sustaining. (If not completely, then at least to a greater degree than under the status quo.) This allows communities to reduce taxes on labor and capital, thereby improving the economy and increasing employment.

Almost every community practices some form of land value return and recycling. For example, the traditional property tax is a tax applied to the assessed value of buildings and the assessed value of land. That portion of the property tax applied to land values returns these publicly-created values to the public sector where they can be recycled to help make infrastructure financially self-sustaining.

If communities were more vigorous in returning land value to the agencies that created them, the following results could be obtained:

The economics of sharing, as expressed by land value return, has been used successfully in both rural and urban communities. It contributed to the success of irrigation districts in California and flood control projects in Ohio. Cities utilizing this approach, such as Harrisburg Pennsylvania, have reduced the number of vacant lots and boarded-up buildings while enhancing housing affordability. Though the tax shift isn’t hugely popular yet, it has been endorsed by the Sierra Club, Friends of the Earth and other environmental and social justice organizations. Herman Daly and John Cobb also endorsed it in their book, For the Common Good.

Employing the economics of sharing more widely would be a good way to show that “ethical economics” is not necessarily an oxymoron. It might even allow people of different political perspectives to find common ground for solving real environmental and economic problems while reducing tax burdens as well. Would this work in your community? Are you willing to help make it happen?