In an unexpected move last week, state health officials proposed setting new enforceable limits for four PFAS-class “forever chemicals” found in public drinking water.

If the recommendation is formally adopted, all of the state’s public water systems will soon be required to remediate when any of six PFAS compounds — up from two today — exceed maximum contamination levels.

Environmental activists were caught off guard.

They had successfully pushed for a new law that will require every public water system in the state to notify customers when levels of 23 PFAS chemicals exceed limits set by the state Department of Health. But the law only requires notification, not action to clean the water.

Now the DOH staff supports required remediation — as well as notification — for four of the 23 chemicals named in the law.

“They were not required by the law to make any new MCL (maximum contamination levels). We’re very pleased they acted proactively,” said Rob Hayes, director of clean water for Environmental Advocates of New York.

While Hayes and other activists want even lower MCLs than the DOH staffers proposed, some members of the state’s Drinking Water Quality Council may push in the other direction.

When it meets late next month, the council is expected to vote on specific MCLs for the four specially targeted PFAS compounds and on notification levels for the other 19. State Health Commissioner Mary Bassett has the final say on whether to adopt its recommendations.

The law requires that draft rules for PFAS notifications be in place by June 17.

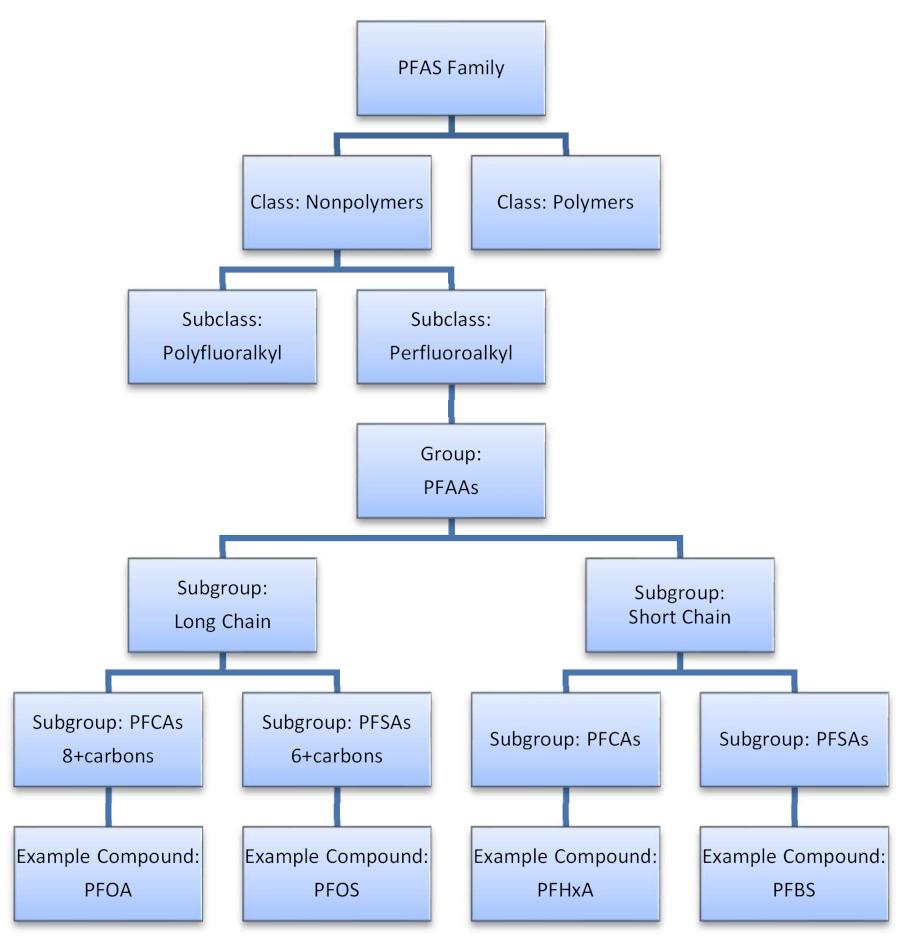

PFAS is shorthand for a class of more than 5,000 chemicals used to make a host of products, including nonstick cookware, stain-resistant rugs and furniture, food packages, weather-repellent outdoor gear, cosmetics and firefighting foam.

They persist for years in the body and have been linked to cancer, liver damage and immune system impairment at concentrations measured in parts per trillion.

While federal regulators have dealt with PFAS contamination in fits and starts for more than a decade, New York was forced to focus on the issue in 2015 after a drinking water crisis exploded in Hoosick Falls, 30 miles northeast of Albany.

Dangerous levels of the compound PFOA were discovered in private wells and the town’s public drinking water. The pollution was traced to a local Saint-Gobain Performance Plastics plant.

The administration of former Gov. Andrew Cuomo was initially criticized for its delayed response. But it did launch a rigorous investigation, establish the Drinking Water Quality Council to advise the DOH and seek enforceable limits on PFOA and PFOS — two of the most common PFAS compounds. In 2020, an MCL of 10 parts per trillion was formally adopted for each one.

All of the state’s water systems (about 3,000) must now screen for those two compounds and take corrective action if the MCL is exceeded for either. Tests showed that roughly one-third of those systems had traces of PFOA or PFOS, as well as other dangerous PFAS compounds.

On Mar. 10, officials from the DOH’s Center for Environmental Health urged the council to set MCLs at 10 ppt for four other compounds: PFHxS, PFHpA, PFNA and PFDA. (That was a major shift from last October when they had suggested 20 ppt as a mere notification level for PFHxS, PFHpA, PFNA. They said the notification level for four other PFAS compounds could be set as high as 200 ppt.)

Dr. Gary Ginsberg, the center’s director, told the council that the new MCL recommendations were based primarily on studies of non-cancerous health effects of PFAS on animals. “We don’t have any evidence one way or the other on the cancer potential of these four compounds,” he said.

Ginsberg said the recommended MCLs provide a wide margin of health protection and should not be viewed as a bright line between safe and unsafe tap water.

At least a dozen other states have taken steps to address the four targeted compounds in drinking water. New York is among the leaders of the growing movement.

Preliminary tests show that about 70 New York water systems would exceed the proposed MCL of 10 ppt for at least one of the four targeted chemicals. The DOH did not respond to an email from WaterFront seeking the names of those local water systems.

The agency has long been reluctant to share its PFAS data with the public.

Ginsberg acknowledged that PFAS compounds make their way into groundwater and public drinking water systems from hot spots that may include industrial sites, toxic waste dumps, landfills, firefighting training sites and other community sources. Sewage sludge spread on farm fields is a major problem in Maine and other states, possibly including New York.

Ginsberg said the DOH has built a PFAS data base that contains “over 70,000 data points,” which is currently being organized for public viewing. “We do have plans to go public with that as soon as we can, hopefully later this spring,” Ginsberg said.

When the DOH identifies PFAS in drinking water, it notifies the state Department of Environmental Conservation.

“They let us know,” said Dereth Glance, the DEC’s deputy commissioner for environmental remediation and materials management. “Our team is on the ground doing site investigation and beginning to figure out the feasibility of remediation.”

The DEC has surveyed hundreds of industrial firms and fire fighting stations to learn about their use of products containing PFAS.

In 2017 the DEC obtained $500,000 in state funding for a program to collect firefighting foam laced with PFOA and/or PFOS from dozens of municipal fire departments across the state.

Collections were centralized in Syracuse and then shipped off for disposal. The DEC favored incineration, and it often contracted with Cycle Chem in Lewisberry, Pa., to have it burned.

But incinerating PFAS is a highly controversial practice because it’s often ineffective and tends to send the contaminants wafting into the air.

In 2018 and 2019, a Norlite facility 10 miles north of Albany burned at least 2.4 million pounds of firefighting foam imported from military sites in 25 states. The DEC has claimed that it was in the dark about the activity and halted it when it found out, but agency emails paint a more complex picture.

At the former Seneca Army Depot in Romulus, tests from wells near a firefighting training center showed PFOA levels as high as 89,000 ppt.

Because plumes of PFOA appeared to be headed from the depot toward Seneca Lake, the environmental group Seneca Lake Guardian sought the results from the state’s followup testing of nearby water wells.

When state officials declined to promptly provide them, SLG sent its own samples of public drinking water from six sources in Schuyler and Seneca counties to a University of Michigan chemical lab to test for PFAS chemicals. The results showed combined PFAS totals ranging from 4.1 ppt to 21.0 ppt for the six sites.

Public alarm prompted local public officials to order retests by a different lab several months later, and they showed lower results.

Landfills in the Finger Lakes region may also be contributing to PFAS in drinking water, the Sierra Club and others charge.

For example, a 2018 report on PFAS levels at the Hyland Landfill in Allegany County showed PFOA at 2,510 ppt and PFOS at 326 ppt. All four PFAS chemicals that may soon have MCLs were also detected.

Hyland has recently applied to the DEC for a major expansion, but it is unclear whether the DEC intends to include PFAS contamination in its environmental review. An initial scoping document for that review does not include the issue.

The Hakes C&D Landfill in Steuben County is also seeking permission to expand. That facility’s 2019 annual report shows water sample tests found a PFOA level of 940 ppt. Two other PFAS compounds were reported at 2,200 ppt and 1,600 ppt.

Meanwhile, on Long Island, PFOA of 2,390 ppt was detected in leachate from the Brookhaven Landfill in 2017 tests, according to an April 26, 2021 memo by the DEC obtained by Dr. Kerim Odekon of the Brookhaven Landfill Action and Remediation Group.

Odekon said he has been frustrated in his efforts to obtain more timely data on that landfill’s PFAS concentrations.

“Through six months of FOIL (Freedom of Information Law) requests to DEC I finally got PFAS testing results from 2017 for monitoring wells surrounding the landfill,” said Odekon, who practices internal medicine at Stony Brook University Hospital. “Since 2017 this was never retested.”

In September 2019, the DOH received a federal grant to study whether landfills are sources of PFAS groundwater contamination.

But when Rachel Treichler, a Hammondsport attorney, filed a FOIL request for results from that study, the DOH denied her request.

“The research project is ongoing and no project results or conclusions have been established at this time,” the agency wrote in a March 8, 2022 letter. “It is suggested that you re-file your FOIL at a later date.”

Sewage sludge spread on farm fields in upstate New York could be at least as big a source for PFAS groundwater contamination as landfills, Ann Finneran of the Sierra Club Atlantic Chapter told the Drinking Water Quality Council last week. But state data on sludge spreading is not readily available to the public.

Council members sounded generally supportive of recommendations to seek MCLs of 10 ppt for the four PFAS compounds, while members Sarah Weyland and Chris Lake favored MCLs as low as 2 ppt.

Lake and many environmental groups, including EANY, would also prefer to set an MCL for all PFAS compounds combined.

As for notification levels for the 23 compounds named in the law, Hayes of EANY said they should be set far below the levels of 20 ppt and 200 ppt DOH officials had suggested in October. Better to set them at 2 ppt or as low as technically feasible, he said.

Council member Lori Emery and Stan Carey cautioned that the accuracy of laboratory tests for PFAS concentrations as low as 2 ppt can’t be guaranteed.

“Trying to push these (testing) methods down to the lowest of the low can lead to inaccuracies, which could also alarm the public unnecessarily,” Emery said.

Carey, the Massapequa Water District Superintendent and Long Island Water Conference Chairman, cautioned that new regulatory burdens will be costly.

“I’m not trying to put money ahead of protecting public health,” Carey said. “But times are certainly different. Water suppliers are seeing 30-70 percent increases across the board for everything related to water treatment.”

He said the DOH needed to update its study on the cost of compliance.