This article was originally published on Common Edge.

Jeffry Burchard explores in his essay the "opportunity found by extending the life and purpose of viable existing buildings", that have shaped our cities. Arguing that "we have an abundant supply of buildings", the author proposes four essential steps to transform existing buildings.

Existing buildings are full of risk and opportunity. That risk can be revealed in physical or functional deterioration and even eventual failure. In some cases, this failure is devastating, as we have just witnessed with the tragic condo tower collapse in Surfside, Florida. But there’s also immense opportunity found by extending the life and purpose of viable existing buildings, as they are uniquely positioned to engage our cultural values, memories, and aspirations.

ODA Imagines the Future of the Streets of New York, Introducing Public/Private Spaces and a New Pedestrian ExperienceAt any given time, we inhabit a fraction of the available space in our buildings. This is not surprising when we consider how many different buildings we use on a daily basis: home, office, grocery store, school. This spatial extravagance was underscored by the pandemic and our surprising ability to do so much at home, where all of the activities of contemporary life were suddenly consolidated to one place.

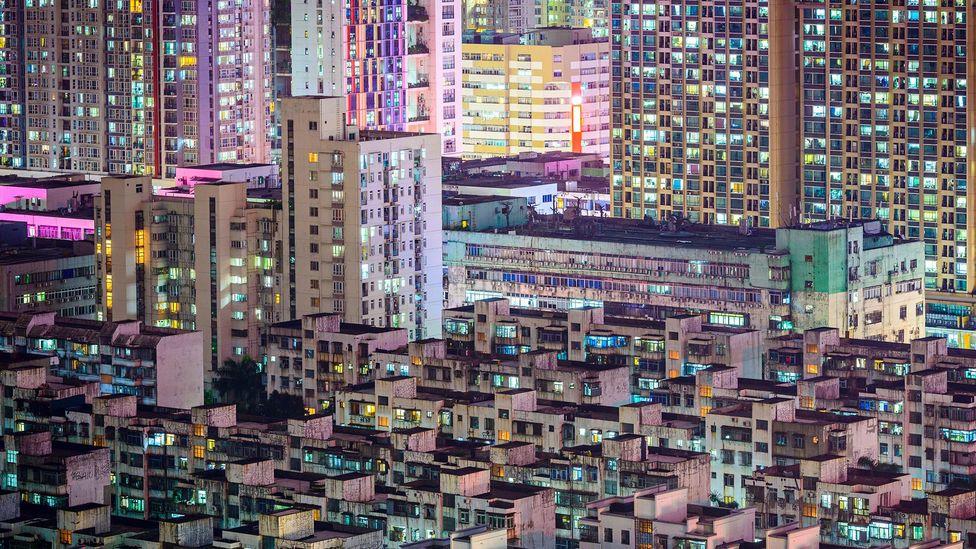

And yet we’re still constructing a lot more buildings. Guidehouse Insights estimates that total global building stock will grow from 1.7 trillion square feet in 2020 to 2.1 trillion square feet in 2030. This increase may be the biggest building boom in world history. In the same time period, the United Nations predicts that the global population will increase by a comparatively low 8.9%, meaning the ratio of built space to humans is increasing. While a percentage of that growth may go where it is needed most, such as providing basic building provisions for those in dire need, a huge chunk of the growth will be deposited in areas where there is already an excess. Seeing this situation as a problem is not straightforward, since many of today’s needs—affordable housing, schools, hospitals, and other basic services, in underserved and ignored communities—are considerably underprovided for by our existing buildings.

Ideas abound for how to get more out of our building infrastructure as humanity establishes new routines post-pandemic and in the era of a global carbon consciousness. These numerous schemes include reusing office buildings like homes, permanently locating office space in the home, co-living solutions, introducing different live/work cycles to spread high-traffic use over the day, balancing online and in-person activities, utilizing smart building technologies to increase the usefulness of spaces while reducing carbon footprints and designing buildings and rooms to do more than one thing. Theoretically, all of these point toward more regularly occupied buildings, thereby reducing the need for redundant square footage.

At the same time, architects, owners, developers, government, institutions, and society at large are appreciating more than ever the full potential in our existing buildings for their embodied carbon, cultural value, historic importance, urban fabric, collective memory, and unreproducible craft. This appreciation has proved most useful when paired with an acknowledgment that in many cases continuing the use of some existing buildings may be impractical (the financial and environmental resources required to save a building or its parts are misaligned with required outcomes); imprudent (climate change represents an imminent and insoluble danger to that building); or in some cases, even immoral (existing buildings, like monuments and urban systems, can come to represent or result from systemic racism and social injustice).

Between these two poles of value and hazard is the more straightforward fact that many existing buildings are simply unfit for what we need them to do. This unfitness frequently shows up in common technical problems: insulation that doesn’t meet energy code, rooms that are just too small, an entrance on the wrong side of the building, a lack of universal access, too much glass, not enough glass, etc. But these deficiencies can also show up in major structural and other life-safety issues that put occupants and the public in grave danger.

The two figures presented below are from Stewart Brand’s How Buildings Learn. Published more than a quarter-century ago, they remain almost perfect (more on the “almost” in a bit). In the book the first diagram is accompanied by this statement: “Add up what happens when capital is invested over a fifty-year period: the Structure expenditure is overwhelmed by the cumulative financial consequences of three generations of Services and ten generations of Space plan changes. That’s the map of money in the life of the building.” In other words, buildings can cost significantly more to maintain and use over their lifetime than they do to build in the first place. This may be mistakenly seen as an argument for new buildings, with optimistically low lifecycle costs, but it should instead be seen as an argument for continuing to use existing buildings, which are already the repository of substantial investments captured in their cost, carbon, system, labor, and cultural footprints.

In the illustrations above, the second diagram shows the multiple layers of a building that may need renovation or replacement over the structure’s life. This illustration utilizes thicker lines to demonstrate resilience (the probability that the layer will fail) and permanence (the difficulty of replacement). According to the diagram, “Structure” should be the least likely to fail and is also the most difficult to change. On the other end, the “Stuff” (loose furniture and fittings) of a building may change rapidly. In between these are the “Skin” (facades) and the “Services” (all of the mechanical, plumbing, electric, HVAC, AV, IT, and lighting systems), both of which have relatively short life spans and regularly need maintenance, minor fixing, or wholesale replacing. And then, finally, there’s the “Space Plan” (Floor Plan), or the layout of rooms and circulation, which Steward Brand identifies as being the most likely to change besides the furniture.

These diagrams point to a couple of conclusions. First, unless a building is to be torn down upon any initial signs of unfitness, additional investment in the building is inevitable, if not natural. Second, there are specific layers of the building and times in the building’s lifecycle to which these investments may be most effectively applied.

Unfortunately, the typical approach to existing buildings is to actually wait (often as long as possible) until multiple layers have noticeably and severely deteriorated before beginning the process of remediating any single layer. Sometimes referred to as “deferred maintenance,” the collection of fixes have a financial price that grows larger the longer the maintenance is deferred. All the while, the deterioration gets worse.

The reasons for deferring action are most often linked to cost, alternate priorities, faulty presumptions on the effect on human safety, lack of information, general ambivalence about poor functionality, and the potential for interruptions in the building’s regular use. But an approach that waits until multiple layers have deteriorated before fixing any not only increases the likelihood of individual layers failing for lack of attention but also increases the likelihood that total replacement is seen as the more effective solution. Indeed, it appears that the structural repairs for the recently collapsed South Champlain Tower in Surfside, Florida, were likely part of a larger package of deferred maintenance work that took too long to identify, agree upon, and fund. Total replacement of aging and unfit buildings is seen time and again, such as the Health and Ag Buildings in Trenton, New Jersey, shown below, which were recently demolished to create a “redevelopment” site.

Let’s revisit Brand’s “Shearing Layers of Change” diagram and its “almost” perfect status. The diagram includes SITE as the thickest line without any arrows, and by this Brand means the physical ground or geographic setting of a project. His 1994 assertion that this is the slowest layer of change is suspect today, given observable climate change and the scientific fact that geographic settings are changing radically and relatively fast in some areas of the world. While true that the pace of this change is typically slower than the wear and tear of furniture, it’s not necessarily slower than the resiliency of structure. A modification to the thickness of the SITE line is required today to reveal more instability in this layer.

We can also add one more line that surrounds the entire diagram called SocioCultural. This thin, wobbly line, with many arrows, close together and pointed in contradictory directions, demonstrates instability and substantial change over time. Simply put, it shows that the values of the people that use, see, appreciate, acknowledge, and generally constitute necessity for the building today are unlikely to be in perfect alignment with those values that were present at the time of the building’s design or construction.

In Buildings-In-Time, Marvin Tractenberg explains this inevitable separation of a building from the values that continuously change around it. He distinguishes between the “life of a building” and what he calls the “life-world of a building.” This life-world is that wobbly, multicolored, sociocultural line. And it represents how the moral and ethical values of a society change over time and translate into what we need and want a building to be, to do, to mean—how any society forms architectural ideas and places values on the Vitruvian trifecta of commodity, firmness, and delight.

Unlike the other layers, which are physical and exhibit the effects of deterioration, the sociocultural layer is a lens by which we can define the problem and judge the likely impact of any remedy. For example, classroom buildings featuring large, terraced lecture halls that do not match an institution’s 21st-century focus on hands-on learning should not be simply refurbished but should be entirely repositioned to meet today’s aspirations for learning environments. Multifamily, affordable housing from the 1960s and ’70s, which are structurally deteriorating, may also have functional and aesthetic qualities linked to poorer or redlined communities. Any updates to these structures should exceed the minimum improvements to safety and should engage ideas that might improve quality of life and celebrate, rather than contain identity.

There is a unique opportunity in existing buildings to embrace, reflect, and encourage our current values. In each technical deficiency, we should see not only the opportunity to reshape the value of a single layer but of all the layers. And we must also acknowledge that sometimes the unfitness between a building and its cultural context needs addressing even when there are no apparent technical deficiencies.

It’s also essential that we recognize each existing building to be distinct. Each must be uniquely considered for how we might value both its history and its now, and what this balance means for our future. This is not a call to erase the history of existing buildings. In fact, our current cultural values include championing the preservation and conservation of the authentic layers of many existing buildings—layer by layer or the entire whole—in order to experience, celebrate, and transfer knowledge about our past.

We have an abundant supply of buildings, we’re constructing, even more, the buildings that we have are increasingly unfit, and too often we wait too long to fix them. At the same time, we see that there’s an opportunity to reposition existing buildings as stewards of our history, representatives of our current values, and aspirational models for the future of the built environment. Here are four essential steps for this transformation:

1- We should not let buildings deteriorate past the point of no return.

This is true of a building’s function, structure and systems, and aesthetics. Part of the solution here may be to find novel ways of introducing change more systematically over the life of the building rather than waiting for a collection of “deferred maintenance” issues.

2- Buildings that appear to be gone may not be.

While appearances or financial considerations may initially suggest that total building replacement is the only answer, a closer look at the individual layers of a building may reveal an opportunity for salvaging the existing.

3- We should utilize every opportunity in fixing existing buildings, no matter how small the project, to reflect, underscore, and advance sociocultural and environmental values.

The history and special characteristics of existing buildings can be best celebrated by ensuring that their continued use is fit for both the functions of today and the aspirations of tomorrow.

4- This effort calls upon architects to be what we are best at informed experts and problem-solvers, agile and inventive in the specific situations every project presents.

Communities respond when someone with recognized experience understands and can reflect their problems, ambitions, and concerns—that is to say, their values. Getting this right tells them that they’re getting the best of what architecture offers. It empowers them and provides architects all the creative and artistic license they need, while holding in check conceited, rehashed, reused, and tired ideas. This is essential, as the characteristics of existing buildings are baked into a community’s lived experience and memory. There is a well-understood and deeply appreciated relationship between buildings and the community values that surround them.