The lesson embedded in Pace Gallery’s How I Learned About Non-Rational Logic, an exhibition of David Byrne’s art, is spelled out in a wall-sized artist statement at its entrance. For visitors who can still catch this breezy, trippy show before it wraps up its six-week-long run this Saturday, figuring out the title’s significance from the works themselves can be more rewarding than relying on the autobiographical explanation. Byrne’s nattily sketched word associations, surreal cartoons, and thought diagrams — also collected in A History of the World (in Dingbats) Drawings and Writings David Byrne (Phaidon Press 2022) — nod to art making as high-spirited brainstorming and insightful deviations.

The fact that mental detours serve as this show’s unifying theme will be no surprise to any visitor with passing knowledge of Byrne’s multimedia career. Like the drawings and writings at Pace, Byrne’s output has involved creative sleights of hand that only appear effortless due to decades of savvy refinement. From his days as a two-time art college dropout turned frontman and chief songwriter for the punk-era juggernaut the Talking Heads to his current Broadway turn deconstructing the pop concert into postmillennial musical theater through the stripped down, gymnastic choreography of American Utopia, Byrne exploits our country’s homegrown conventions. His subject matter ranges from advertising bromides to self-help talk to religious fundamentalist exhortations, their languages reframed into funkier, more skewed grooves and configurations that — like these spur-of-the-moment drawings and pictographs — make America’s delusional optimism seem credible again.

Byrne’s public reputation for proposing counterintuitive hopefulness provides another subtext in How I Learned About Non-Rational Logic. Although he enjoys a celebrity’s comfortable perch in gentrified New York, the artist has publicly inveighed, insightfully and determinedly, against the city’s ongoing encrustation in Midas gold. In response, less famous and well-connected fellow artists — including some in this publication — have charged him with ignoring creative communities and cultural initiatives thriving beyond Gotham’s gilded zip codes. But living in the glass house of an elite Manhattan gallery, as Byrne does, doesn’t mean you can’t throw rhetorical stones at the creepy commodification of nearly every facet of daily American life, provided you aim those objections at the right agents.

That’s not to say this exhibition is political. It isn’t. But there’s more than a winking nod to the inbuilt contradiction in showing unassuming drawings and writings — most made spontaneously by Byrne with a mere pen or pencil on archival paper — in an elite art gallery with global outposts. Set directly across from the ostentatious Chelsea skyline visible through the gallery’s 7th-floor skylights and ceiling-to-floor windows, Byrne’s small-scaled and spare drawings — many dating from the city’s grueling lockdown period in 2020 — may remind us (and maybe reminded the artist as well) that art can be created wherever you find yourself entombed, and by using whatever tools you have in that bunker.

So, is Byrne’s art any good? Stylistically, the best drawings and most interesting verbal pictographs land somewhere between the interrogative visual adventures in Saul Steinberg’s virtuosic drawings and the sometimes overhyped calisthenics of Keith Haring’s charming silhouettes. As the exhibition spotlights the most rudimentary level of Byrne’s visual repertoire, it’s akin to observing, in any given city or small town, a daydreaming bus passenger with pen in hand, drawing or scribbling excitedly in a moleskin notebook. So the “non-rational logic” to which Byrne alludes is the fertile mindlessness that goes into making art on an everyday basis.

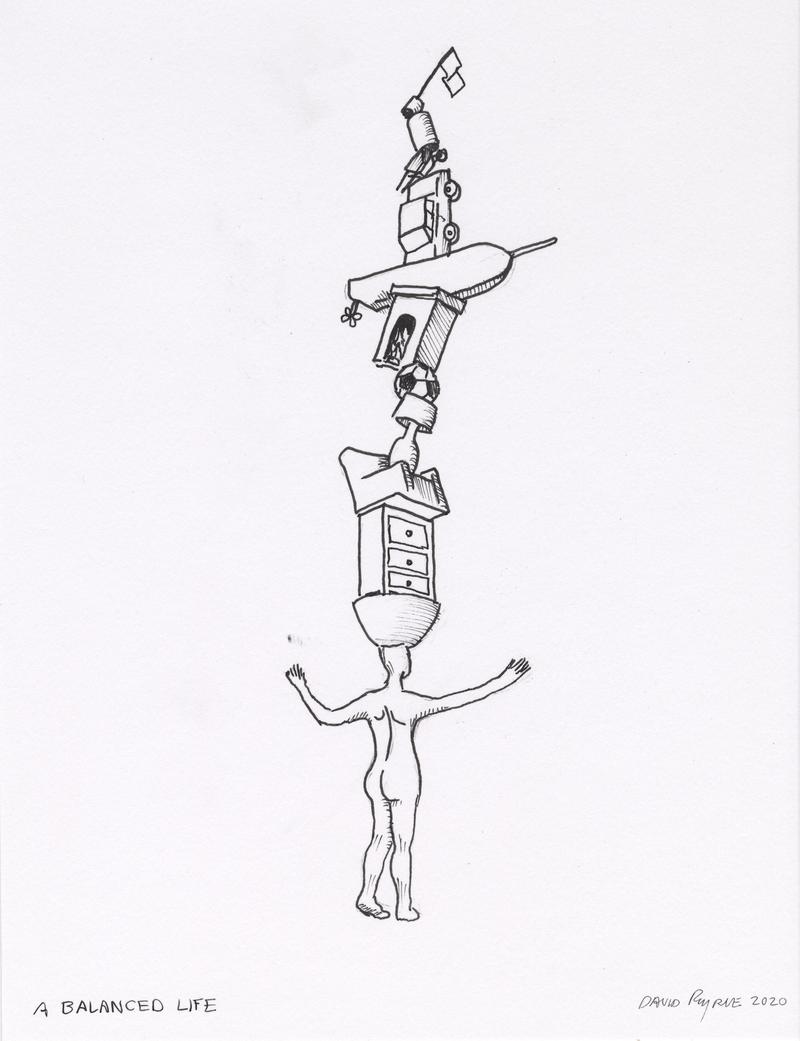

And so Byrne shows that the pen has reasons that reason can never know. A still-life doodle of a woolen winter cap can metamorphose hairy human limbs and look ready to take a winter’s walk. A self-assured pigeon gazing into its wardrobe mirror can see its neurotic human double staring back with reciprocal envy or admiration for what they both almost are, or aren’t. Visual engimas like these play out through the drawings’ consistently disarming humor. What causes the agony in Byrne’s Mr. Potato Head as he grimaces and rears backward on skinny avian legs? Is the giant finger reaching down for a pill-sized smart phone that of a postmodern Gulliver, texted by Lilliputians who miss his company?

Some of the works that include writing — especially the wall-sized mural that dominates the exhibition space — represent Byrne scattering and then rearranging cultural code words and familial or social labels. One drawing shows that a cocktail bar’s taxonomies can be as intellectually productive as a chemist’s periodic table. Other word associations are set within the roots and branches of trees to reveal how pre-given categories can, without much conscious thought, outgrow or uproot former hierarchies; still other pictorial lists show how the subconscious mind classifies and distorts markers of human progress or worldly success.

Stop making sense, Byrne famously sings in the Talking Heads’ underground dance hit “Girlfriend Is Better” (1982). And in the American decades since Byrne first plied his musical trade in New York’s squalid Lower East Side clubs — in a far more egalitarian economy than ours and in a city that then had an undeniably more diverse, de-institutionalized artistic ecosystem — the willfully ignorant among us have increasingly seized power by denying empirical facts while claiming to be most enlightened, turning rationality ever more on its aching head.

So this lightheartedness is a tonic for our times even as the exhibition poses a serious question: Can the simplest gestures in art and writing revive optimism amid the dangerous nonsense and simplifications that pass for cultural and intellectual exchanges these days? In the liner notes to his album American Utopia (2018) Byrne, in the pre-pandemic Trump-era, comes close to eulogizing that American tradition of hope, before returning to the premise that “to be descriptive is to be prescriptive.” If you unpack that sentiment further in light of these drawings and writings, it’s less a naïve platitude than it sounds. And it makes me wonder what else art is for, but to remind us that what we call “being reasonable” is too often our expedient alibi for not using our imagination.

David Byrne: How I Learned About Non-Rational Logic continues at Pace Gallery (540 West 25th Street, Chelsea, Manhattan) through March 19. The exhibition was organized by the gallery.