Stan Wash, dwarfed by towering metal shelves stocked with faucets and toilet seats, raises a small glass of butterscotch-colored liquid to his lips, takes a taste, and gasps.

“WHOO! Oh my goodness! UGH! That’s so tannic!”

We’re standing in a cavernous plumbing warehouse in Gary, Indiana, where Wash and a partner, Zach Getzelman, press, age, and bottle wild-fermented apple cider under the label Overgrown Orchard.

“That’s gonna need some time,” says Getzelman.

Wash pulled the sample from a bunghole atop a repurposed whiskey barrel, which they’d filled with their own fermented GoldRush apple juice. He picks up a glass pipette—otherwise known as a wine thief—and draws another measure from an old sauvignon blanc barrel. This juice was pressed from Golden Russets, foraged crabapples, and fruit they’d harvested last season on a four-acre orchard a quarter mile to the southwest.

This one has had more time to develop in the barrel, but still isn’t quite ready. “Wow,” says Wash. “That’s delicious. It’s got some real sharp, hot notes to it. It’ll age and blend well, but it needs time. That’s what new juice tastes like.”

“But it’s good juice,” says Getzelman. “Caramel and vanilla.”

I spent a day at Overgrown Orchard last month, eating cheese and tasting finished, bottled cider—and also barreled ciders still maturing after the wild spontaneous fermentation that’s begun with naturally occurring yeast found on apple skins, in the air, and on the oak. Each one had its own distinct nose and flavor, but overall what distinguished them from the one-dimensional, canned supermarket ciders that dominate the U.S. market was their dry fruitiness, food-friendly acidity, and very often a whisper—sometimes a gust—of farmhouse funk.

American cider in the U.S. is popularly viewed as a sweet, gluten-free alternative to beer. And though there’s a thriving parallel independent craft cider movement with plenty of interesting and delicious things to drink, the vast ocean of it is produced quickly, under strict control, from sweet, pasteurized apple juice or concentrate, spiked with commercial yeast strains and added seasonings.

It wasn’t always this way. America has an old cidermaking tradition—interrupted by industrialization and Prohibition—that was more akin to ancient cidermaking in northern Spain, northern France, and the UK. Slowly, amid the last decade’s cider boom, a handful of cidermakers have returned to old methods that are closer to natural winemaking than brewing.

“We’re essentially winemakers,” says Wash. “It’s the exact same methodology, and it’s extremely simple: you press apples and you let the juice age.” Cidermaking for Wash, who is a commercial litigator for a major law firm during the week, started as a hobby that quickly got out of hand.

Seven years ago he stumbled across an unfamiliar fruit at the Nichols Farm stand at the Federal Plaza farmers’ market: a Cox’s Orange Pippin, an heirloom English dessert apple that sent him down a rabbit hole of forgotten varietals with names like Ashmead’s Kernel, Roxbury Russet, and Transcendent Crab; many with sour, bitter, and bittersweet flavors that would never pass in the produce section. “I was like, ‘Oh my gosh. There are apples that exist almost exclusively for making cider.’ There was this epiphany: you go up to any dude with a neck beard and he can name five hop varietals, but ask if he likes cider and, ‘No, I don’t like sweet beverages.’”

Wash read all the cider books he could find, began listening to cider podcasts, and he skipped work for three days to attend CiderCon 2015, the annual conference of the American Cider Association, held frequently in Chicago. By then he had enough confidence to give it a go. He bought a $1,500 mill and press from a farmers’ supply site, and, “I went to the farmers’ market and walked up to some apple seller and was like, ‘Hey can I get 400 pounds of apples?’”

Wash hit up his old law school classmate Getzelman, who he describes as “a consummate drinker.”

“‘Hey, do you wanna crush apples in my backyard?’” They purchased carboys, a bottler, and sanitizing equipment from a home brew shop, where the clerk told him it was the largest order they’d ever filled. “That’s a sign that my hobby is absolutely out of control.”

They made about 15 gallons the first time around using conventional methods and commercial yeast—even dry-hopping a batch in line with a nascent fad adopted from brewers. “It was garbage,” says Wash. “But it gave us enough courage to keep going. I didn’t have kids yet, so I was like, ‘Why don’t I waste my future children’s college fund buying stuff?’”

There are a lot of barriers to entry to making the kind of cider Overgrown Orchard has sold over the last five years. It’s easier if you’re already a brewer or vintner who knows how to ferment things; or a farmer growing the uncommon sharp (or acidic), bitter (or tannic), or bittersweet and bittersharp apples needed to make real cider. Wash and Getzelman were neither, but they did have Wash’s plumber brother, who begrudgingly lent them warehouse space for the $16,850 Austrian Voran mill, the four 220-gallon egg-shaped tanks they use for primary fermentation, and the increasing numbers of used oak barrels stacked in the shadows of the toilet seats and faucets, where apple blends mature anywhere from 12 to 18 months before bottling.

At first it was difficult to find the proper fruit, but they made relationships with farmers and foraged for many of the bitter crabapples, or “spitters,” whose tannins, with time, age into the pleasant tactile astringency that’s such a prized quality in good wine.

“I keep orange vests in the back of my car and a ladder,” says Wash. “I have these big onion bags that can hold probably a hundred-plus pounds of apples. There are awesome crabapple trees in Old Town. If you put on a vest, nobody says anything to you.”

The more they learned, the more they gravitated toward wild fermentation, minimizing intervention by letting natural yeast do all the work. There are even more barriers to this kind of cidermaking; it takes much longer, and it’s more unpredictable.

But they did have land—or rather, Wash’s brother did. Over two years they planted more than 400 trees—67 varieties from all over the world: sweet French Fenouillet Gris; sharp Danish Gravensteins; bittersweet English Dabinetts; bittersharp Russian Dolgo Crabs; and the sweet Indiana native Winter Banana.

The trees, in various stages of growth, line up neatly southwest to northeast, wedged between freight tracks, I-80/94, and the shallow Deep River, which empties into the East Arm Little Calumet. Wash is full of self-deprecating jokes about the postindustrial terroir of Gary, the weeds, and the diesel fumes. But he’s discovered herons, tadpoles, fish, and shrimp in the river. Beavers have marauded the orchard, taking more than a dozen trees, and deer have attacked them too, but the most the partners do to intervene is to mow the weeds between the rows so the field mice, which gnaw on the tree bark, can’t hide from the raptors that keep them in check. They don’t water, fertilize, or use pesticides.

Meanwhile, honeybees from 60 hives on the riverbank help pollinate in the spring. Last summer some of the honey fed the yeast that carbonated their 2019 Ella, blended from Golden Russets, Muscadet de Dieppe, and Winesaps. It tastes like a dry champagne with a hint of fermented caramel.

The silty loam produces high-acid, low-sugar apples. The same apples grown in a warmer climate, like say, Virginia’s, would produce more residual sugars, theoretically leading to sweeter ciders. But Wash is among the cidermakers who believe that terroir is best expressed by what happens in the cider house, more than the orchard.

Last fall, Wash, Getzelman, and a third partner, Jeff Guerrero, along with a posse of volunteers, picked close to a thousand pounds of apples, which pressed about 2,000 gallons of juice. Various blends were pumped into the open-topped egg fermenters. At this point most cidermakers (and winemakers) would add sulfites to the juice, which would kill off the indigenous yeasts. From there they’d “pitch” a commercial yeast strain on this liquid blank canvas, which would quickly yield a very predictable, consistent result.

Consistent, or consistently boring?

Overgrown Orchard doesn’t add sulfites to their juice, simply allowing remnant apple skin and pulp to sink to the bottom of the tank, while the natural yeast devours the sugars, releasing CO2 and ethanol. “When you do wild fermentation you’re opening the door and inviting hundreds and hundreds of yeasts to the party,” says Wash.

They don’t leave the juice on these “lees” for too long, so after about a month, it’s racked off into various used oak barrels to age further. Overgrown Orchard uses everything from old pinot noir and chardonnay barrels, to ones used to make whiskey, gin, and calvados. Their ciders pick up just a hint of those traits as they develop the phenols and esters that contribute fruit flavors without residual sweetness. The cider is carbonated in the bottle via the traditional méthode champenoise by adding a sugar syrup, or liqueur de tirage, to revive the yeast, which yields CO2.

Much like most natural wines, they’re never the same from year to year, and they never stop changing in the bottle. Monument, named for the Illinois Centennial Monument in Logan Square, is their “middle of the fairway” cider; a highly acidic, creamy, effervescent blend. Each year they select a set of barrels that will archive this basic profile—but every year it’s different.

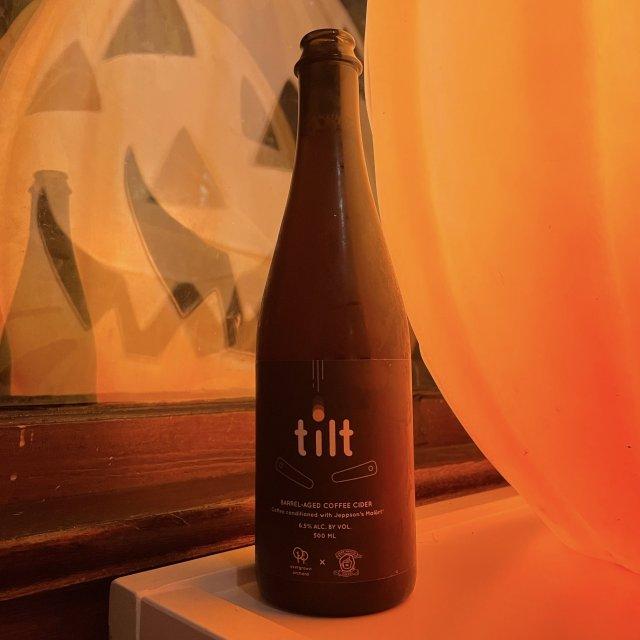

The same is true with the much funkier, less carbonated Joujou, which is aged in calvados barrels and tastes a bit like a green Jolly Rancher. Resist is aged in whiskey barrels, and its cherry-graham cracker notes are underscored with a kiss of carbon. Black, a collaboration with brewer Ørkenoy, benefits Black Educators Matter and is a combination of Winesap, wild crabapple juice, and a saison made from wild yeast harvested from a Yucatán cave. It’s among the funkiest things they’ve made, with huge hits of pineapple, strawberry, and orange.

“We get tons of acid,” says Wash. “And we get huge fruit esters. So we get a lot of berry flavors, a lot of stone fruit, like peach. It’s not sweet, but it’s real fruit-forward with a perceived sweetness. Crisp, and not terribly different from northern Spanish wines or drier Austrian or German wines that lend themselves well to food pairings and patio crushing.”

Wash, Getzelman, and Guerrero have released these and other new vintages each year since 2017—you can order many of them online. They’ve also appeared on a handful of restaurant lists and in shops like Bottles & Cans and Bitter Pops. One of their most reliable stockists is Logan Square cheese shop Beautiful Rind, though they’re largely absent from the most obvious places you’d expect to find them. COVID interrupted their campaign of wine shop tastings. But even before that it was a hard sell, because even sophisticated drinkers have a hard time wrapping their heads around the idea that it’s just wine.

“I’ll ask, “Do you want to try some cider?’ and it’s, ‘I hate cider. All I drink is wine.’ Well, surprise. It is wine.’ But that’s not their fault. It’s because 99.9 percent of all cider is made differently.”

And that’s another reason Wash and his partners won’t be giving up their day jobs soon, even though there’s lots of room for growth. When the orchard is up to full speed it’ll produce some 10,000 pounds of apples each year, which will require more employees and more square footage. Wash’s brother has set aside some space for the cidery in a newly constructed bay—but he wants rent.

For now Wash is practicing distraction. “He’s like, ‘Motherfucker, I’m gonna burn this shit. Get it out of my warehouse.’ It’s just, ‘Dude, what a gift I’m giving you. One, you get to see your brother regularly, and two, this is a plumbing warehouse that smells like a beautiful winery. What’s the problem?’”