The public image of palaeontologists as dusty, but rather affable academics, could be due an update. The study of ancient life is a hotbed of unethical and inequitable scientific practices rooted in colonialism, which strip poorer countries of their fossil heritage, and devalue the contributions of local researchers, scientists say.

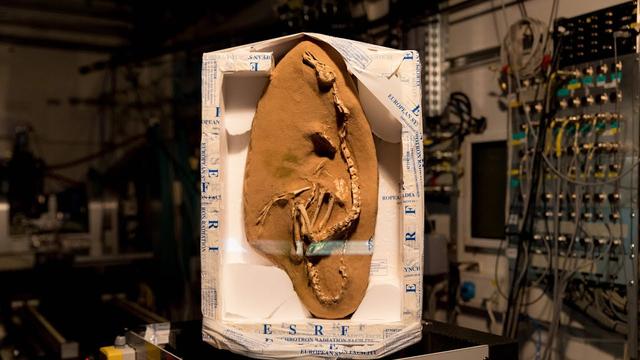

Writing in the journal Royal Society Open Science, an international team of palaeontologists argue that there has been a steady drain of plesiosaurs, pterosaurs, prehistoric spiders, and other fossils from poorer countries into foreign repositories or local private collections – despite laws and regulations introduced to try to conserve their heritage.

For instance, in the Araripe Basin in northeast Brazil – a region famous for its huge array of well-preserved prehistoric fossils, including giant winged pterosaurs – 88% of discovered fossils are now housed in foreign museum collections.

Juan Carlos Cisneros at the Federal University of Piauí in Brazil and colleagues scrutinised paleontological publications of fossils discovered in Brazil and Mexico over the past three decades. These countries have large, and relatively unexplored sedimentary basins harbouring a wealth of fossilised creatures, plants and fungi.

Despite the introduction of strict permits to conduct scientific fieldwork or export fossils from Brazil, and a ban on their permanent export, permit declarations were often missing from studied specimens, and many studies were based on fossils illegally held in foreign collections – particularly in Germany and Japan – the researchers found.

The exclusion of local experts was another common issue. For instance, 59% of publications on Araripe fossils were led by foreign researchers, and more than half of them showed no evidence of collaboration with local Brazilian researchers - another legal requirement.

Such practices amount to scientific colonialism, where lower income countries are perceived primarily as sources of data or specimens for higher income ones, legal frameworks bypassed, and the contributions of local researchers devalued or omitted, they argued.

“It might not be the colonialism we think of, when we imagine 19th-century ships sailing across the Atlantic, but it is still a modern form of neocolonialism where we’re being extractive and exploitative for our own gain at the expense of lower income countries,” said Emma Dunne, a palaeobiologist at the University of Birmingham, and a co-author on the paper.

Doing so, hinders local scientific development and depletes resources that could sustain longer-term economic activities, such as tourism, the team added.

“I think we are often seen as cute characters that wear Indiana Jones outfits, and could surely do no harm. But actually, Indiana Jones is a really good example: one of his catchphrases was ‘this belongs in a museum’ – but what he means is his museum, not a museum in the country he’s collecting the thing from.

“We’d love for individuals to change the way they work, to really focus on creating genuine partnerships that are built on respect for local communities and their interests.”

The team also called for more rigorous journal guidelines and education on research ethics, greater enforcement of fossil laws, and sanctions against those involved in unethical practices. Finally, fossils should be repatriated to those communities from which they have been taken, they said.