Keeping those aging, subterranean arteries from spilling their toxic contents is enormously complicated and costs tens of billions of dollars a year more than U.S. cities can afford to pay. Which is why cities and the service contractors they rely on are deploying an array of technological tools that boast the potential to explore, diagnose and repair sewer systems in new and more affordable ways.

Seattle

$602

Cleveland

$3,000

King County, Wash.

$711

Boston

$898

Chicago

$1,770

Cincinnati

$3,290

Kansas City, Mo.

$2,383

St. Louis

$4,700

$30.97 billion

estimated cost

in total

Washington

$2,574

Atlanta

$1,149

Note: Data is from 2017Source: Environmental Protection Agency

The arsenal includes flying drones, crawling robots and remote-controlled swimming machines. They are armed with cameras, sonar, lasers and other sensors, and in some cases with tools to remove obstructions, using water-jet cutters capable of slicing through concrete, tree roots, and the giant agglomerations of grease and personal-hygiene products known as fatbergs. Some can also fix leaking pipes using plastics that cure via ultraviolet light.

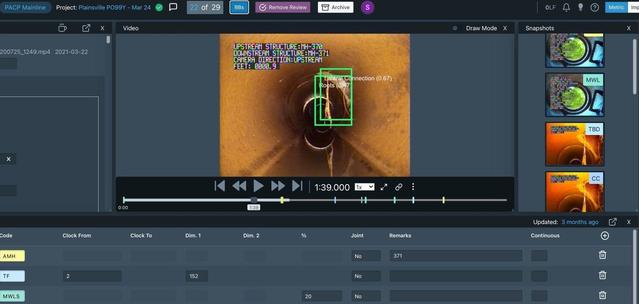

The tools also include artificial-intelligence systems for automating the labor-intensive process of cataloging defects in sewer pipes and storm water culverts, and for giving priority to repairs based on need and location.

Collectively, all this tech represents a major shake-up for an industry that has been slow to change, says Gregory Baird, a former finance chief in charge of water- and wastewater-infrastructure for cities in California and Colorado, and currently a consultant to cities on addressing their aging water and wastewater infrastructure issues. “In the last few years I have been watching the industry, asking, ‘When is artificial intelligence and machine learning going to get water and sewer?’ ” he says. With the introduction of software capable of pulling data from tunnel-exploring robots and automatically identifying flaws in sewer systems, combined with other software that can predict what is likely to fail next, he believes that day is finally here.

The U.S. has 875,000 miles of sewer mains. Hundreds of the municipal wastewater systems made up of these subterranean highways for effluent are long overdue for massive repairs and replacement. The problems include steel, clay and concrete pipes reaching the end of their projected lifespans; storms of increasing intensity thanks to climate change; and ever-more-stringent environmental regulations.

The consequences when systems fail are serious: the spread of disease, the flooding of homes and businesses with sewage, and a reversal of gradual improvements to the health of much of the nation’s streams, lakes, beaches and oceans.

According to the American Society of Civil Engineers, in 2019, the most recent year for which data are available, the total spending for physical wastewater infrastructure in the U.S. was $48 billion, while the total need was $129 billion—an $81 billion shortfall.

The just-passed $1 trillion infrastructure bill includes $55 billion for water-related infrastructure. Less than half that amount is specifically for wastewater, including grants and low-interest loans to cities and states to fix their systems. It’s a lot of money, but a drop in the bucket compared with what both the ASCE and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency say is needed.

One result of these shortfalls is that hundreds of municipalities have been found to be in violation of the 1972 Clean Water Act, leading to action by the EPA. For example, in April of 2021 the city of Houston signed an agreement with the EPA that entails an additional $2 billion in spending over the next 15 years to upgrade its wastewater system and address repeated sewer overflows.

Part of the problem that technology is being used to solve is the sheer difficulty of exploring these labyrinths to determine where the issues are.

Charles Rey, a drone pilot for Flyability, which manufactures a special kind of collision-tolerant drone that can be flown through sewer tunnels, has probed systems beneath cities throughout Europe, Asia and the Americas. One of his most memorable trips was through sewers beneath the Chinese city of Ganzhou, so old that they dated to the Song Dynasty, which ruled from 960 to 1279. “We found stuff they had no idea about, including old stairways,” says Mr. Rey.

While even the most antiquated U.S. sewer systems are a lot younger than that, mystery about what is below ground is common for municipal wastewater systems, says Sam Macdonald, president of Deep Trekker. Her company was founded to build remotely operated vehicles for exploring shipwrecks, but stumbled into unexpected demand in the wastewater industry when contractors began using Deep Trekker’s first remotely operated vehicle to explore drainage pipes. Now, its completely submersible, wheeled pipe crawler is used all over the world to inspect sewers.

Over the past two decades, wheeled crawlers with CCTV cameras have become standard for sewer inspections. Despite substantial competition in the industry from a variety of manufacturers in the U.S., Europe and China, they’re not cheap, in part because they have to be extremely tough, says Jake Wells, director of marketing at Envirosight. Sewer-crawler robots usually cost around $70,000, and must be able to endure many hours a day of grime, grease and corrosive hydrogen sulfide gas, a natural byproduct of the bacterial ecosystems that thrive in sewers.

Speeding up the process of inspecting sewers using these robots by automatically identifying problems in sewer pipes is what the founders of Sewer AI, started in 2019 in Walnut Creek, Calif., set out to do. To initially train its computer-vision system to automatically identify and categorize defects in sewer pipes, the company asked cities for copies of sewer-inspection videos, says Matthew Rosenthal, CEO and co-founder of Sewer AI, which counts Houston among its clients.

Now, the company has a video library of millions of feet of sewer pipe, across more than 100,000 inspections. Fresh data is continually fed into the system from inspections conducted by Sewer AI clients.

HK Solutions Group, which handles sewer inspections for more than 150 U.S. municipalities, ranging from 5,000 people to 5 million, is sending Sewer AI video of 200,000 feet of sewer pipe a month for automatic identification and tracking, says Michael Ingham, HK Solutions’ chief sales officer. The result is that what used to require weeks or months of processing by certified human inspectors can now be accomplished in as little as a day. “It doesn’t require us to have people subjectively grading these sewer systems as to what’s a defect, what’s not, what’s the severity of that defect,” says Mr. Ingham. “The AI just identifies that now.”

Traditional methods for inspecting sewers leave plenty of room for improvement in accuracy as well as cost. Cataloging issues in wastewater systems gathered by human inspectors using crawler robots has an error rate of around 20%, says Mr. Baird, the consultant. “Humans get fatigued, and they miss something because there’s running water in there, and rats, and it’s not intellectually stimulating to watch poo in sewer pipes and sit there thinking that’s going to be the next 10 years of your life,” he adds.

Once municipalities have completely mapped their systems—which can take years—robots from companies like Netherlands-based Sewer Robotics can make repairs without digging up pipes.

What do you consider the most pressing infrastructure needs in your community? Join the conversation below.

After the water-jet cutters blast away fatbergs and other obstructions, a robot can apply a patch—a sleeve that completely covers the inside of the pipe—and cure it with UV light. The process works even if the pipe still has water flowing through it, says Bart van der Zalm, a sales manager at Sewer Robotics. Crawler robots with a variety of attachments have been in use in Europe for years, but the U.S. wastewater industry has been slow to adopt such technologies, he says.

While all of this technology can allow contractors and municipalities to inspect—and sometimes fix—sewer systems more quickly and cost effectively than ever, one thing it can’t do is elevate public awareness of the problem, or the lack of public investment needed to fix it.

“If you drive under a bridge, you can see the spalling concrete and rusting girders,” says Mr. Wells of Envirosight. Sewers are in many ways facing challenges even bigger than America’s notoriously fragile aboveground infrastructure, he says. But their problems are often as invisible as they are severe—until it’s too late.

For more WSJ Technology analysis, reviews, advice and headlines, sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Write to Christopher Mims at christopher.mims@wsj.com